|

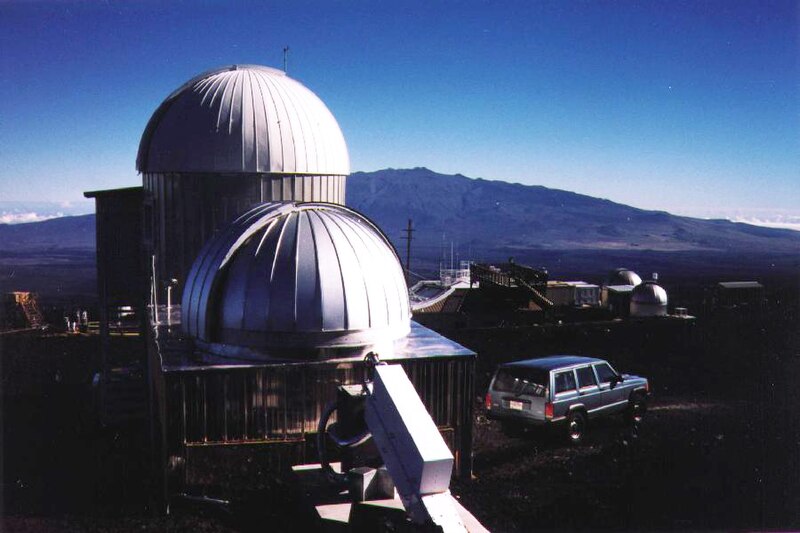

| Mauna Loa Observatory. Photo by Wikimedia Commons |

As I was pondering over the many technologies reviewed so far on energy use and its effect on climate change, I began to wonder how the first scientific measurements of CO2 came about.

Up till the 1950s, scientists had largely believed that

anthropogenic CO2 emissions would be absorbed by vegetation of the ocean, and

would hardly have a measurable impact on climate change (NY Times, 2005). It

was due to the dedicated work pioneered by Dr Charles Keeling (1928-2005) from

the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego that the effect of CO2 on

earth's climate has come to grab the world's attention.

|

Dr Charles Keeling receiving the Medal of Science from

President Bush

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

|

Dr Keeling, in an essay titled "Energy and the Environment" published in 1998, meticulously recorded how he had engaged a glass-blower to customise the apparatus he needed, the long drive to Big Sur State Park in California where he took the first CO2 measurements, and the subsequent initiation of the historical CO2 time-series measurement at Mauna Loa in Hawaii in 1958, which we have come to know today as the Keeling Curve

|

| Keeling Curve from Wikimedia Commons |

Dr Keeling's work on CO2 measurements was fraught with challenges, ranging from technical issues on the sampling equipment to funding cuts from the government. His research nonetheless continued unfaltered. In a paper titled "Industrial production of carbon dioxide from fossil fuelsand limestone" published in 1972, Dr Keeling reported that the cumulative increase in anthropogenic carbon from mankind's industrial and domestic activities was about 18 % of the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere during the late nineteenth century.

Dr Keeling cited a three-fold increase in global fossil fuel consumption since he began measuring CO2, which essentially increased almost six-fold over his lifetime. He came to know Dr Harrison Brown at Caltech. Brown (1954) wrote that "should a great catastrophe strike mankind. the agrarian cultures which exist at the time will clearly stand the greatest chance of survival and will probably inherit the earth. Indeed. the less a given society has been influenced machine civilization. the greater will be the probability of its survival".

Dr Keeling subscribed to Dr Brown's view that mankind should conserve fossil fuel use as a most prudent approach, regardless of whether dire environmental consequences would result from rapid fossil fuel use, given that the danger of global warming would be reduced as well.

As I read Dr Keeling's recollection of his journey, what

struck me most was the passion that he held for science. Perhaps serving as

a gentle reminder to put aside the controversies behind the climate change

issue, and enjoy the pursuit of scientific knowledge in its purest form.

"Why did I

devise such an elaborate sampling strategy when my experiment didn't really

require it? The reason was simply that I was having fun. I liked designing and

assembling equipment. I didn't feel under any pressure to produce a final

result in a short time. It didn't occur to me that my activities and progress

might soon have to be justified to the sponsoring Atomic Energy Commission. At

the age of 27, the prospect of spending more time at Big Sur State Park to take

suites of air and water samples instead of just a few didn't seem

objectionable, even if I had to get out of a sleeping bag several times in the

night. I saw myself carving out a new career in geochemistry." (Keeling, 1998)

Thanks for sharing this Joon - I read an article not long ago that the lack of a US budget agreement was threatening Keeling's curves and was really interested in how they came to be in the first place - Really informative post!

ReplyDeleteHi Darren, thank you for the comment. I most certainly hope that the US government understands the importance of keeping Dr Keeling's work alive!

DeleteHi Joon,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the interesting post! I really enjoyed reading about how the Keeling Curve was born. I found Dr. Brown's observation that should a disaster strike humanity, agrarian cultures that are not indusrialised would be most likely to survive very interesting (what would we do without fossil fuels?).

Cheers,

Katherine

Hi Katherine, thanks for your kind comment.

DeleteI also find Dr Brown's thoughts intriguing. Perhaps we can take it as a call for societies to understand that fossil fuels and comforts of modern technology may one day reach its limits. It may then be prudent for us to be conscious of the need to conserve these precious resources.